July 25, 2016

In January of 2015 I shared my research in an article, “Brotherhood Transcends Civil War”, about the benevolence of the New York Firemen’s Association when they purchased a hose carriage for the Independent Hose Co. of Columbia to help in replacing apparatus destroyed by General Sherman in 1865. This current article focuses on a mystery that has captured my interest to the point I am practically consumed with research that is taking me back once again to the Civil War and the role of firemen during those harsh days of our history. [caption id="attachment_8507" align="alignright" width="240"] Medallion found outside Columbia[/caption]

Many months ago, I was asked by Susan Duncan at the State Fire Marshal’s Office to contact Mr. John Frierson of Lexington County who had possession of some sort of fire department artifact that may have historical significance to the fire service. I immediately reached out to Mr. Frierson who agreed to meet me in Columbia a few days later to show me a find he had unearthed while searching with his metal detector for artifacts near Columbia.

Mr. Frierson and I met at a farm supply store in Columbia where he handed me a box containing his treasure. I was almost speechless when I opened the small box. There, gently laid in a pillow of cotton, was an old fireman’s badge or medallion which was immediately obvious to me to be a relic dating back to our early history.

Mr. Frierson was very gracious and trusting to allow me to take his prized possession with me to begin researching its origin and eventual ownership. After getting home, my wife and research partner, Mary Jo, began looking at its detail with a magnifying glass. We knew from its designed that this was not a badge but rather some sort of medallion. The small metal ornament was imprinted and adorned with a hand-drawn ladder wagon on one side, a hand-drawn hose carriage on the other side, and a hand-drawn steam engine situated at the top of this work of art. Also engraved in its design was a speaking trumpet, a play pipe, ladders, a long-neck lantern, and a fireman’s helmet shield and flames imprinted at the top. Three holes, two at the top and one at the bottom still retaining a clasp, were observed, all lending belief that this item is a medallion rather than a badge. No marking or latch pin is found on the back.

I sent the photograph of the artifact to Daniel Maye, Chief Librarian of the FDNY Library, and Gary Urbanowicz, author of “Badges of the Bravest” and co-author “The Last Alarm: The History and Tradition of Supreme Sacrifice in the Fire Departments of New York City”. And, on a notion, I sent it to Chief Ronny Coleman, historian and former California State Fire Marshal, in hopes these experts could help in identifying its origin and eventual ownership.

They all responded with basically the same opinion: it is old and likely an artifact of the 1800s or early 1900s; it is a medallion much like we may see from early conventions or fire department competitions; ribbons and other labeling attachments probably complemented the main pendant. I am grateful to these gentlemen for their time and opinions.

Next came additional research to discover who, why, and other circumstances leading to its ultimate discovery near Columbia. From my own experience and knowledge, the medallion is not a native find from South Carolina or the South. Under this assumption, I began to research fire department badges and medallions of the North. Interestingly, I discovered that a large number of Northern volunteer firemen served in the Union Army fighting against the Confederate cause. Records from the annals of history reveal that firemen from across Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Lancaster, and York Counties) as well as New York State responded to President Lincoln’s appeal for 75,000 volunteers to defend the Union on April 15, 1861.

Among the most famous Northern groups of fireman to fight in the Civil War was the First New York Zouaves, or 11th Fire Zouaves. This group was organized under the leadership of Col. Elmer Ellsworth, a young Chicago State militiaman who, by the way, was not a fireman. According to writer Donald Collins, Ellsworth desired to recruit volunteer firemen because they were usually disciplined, brave and physically fit. Ellsworth wanted his men to stand out and to be different as soldiers of the Union Army, so he provided these volunteers with fancy uniforms similar to the French Zouaves having short blue jackets, baggy bloomer-like red trousers, reddish brown boots and red fez hats. It is noted that these colorful uniforms also made the firemen who wore them easy targets during the awful battles which were to come.

[caption id="attachment_8508" align="alignright" width="449"]

Medallion found outside Columbia[/caption]

Many months ago, I was asked by Susan Duncan at the State Fire Marshal’s Office to contact Mr. John Frierson of Lexington County who had possession of some sort of fire department artifact that may have historical significance to the fire service. I immediately reached out to Mr. Frierson who agreed to meet me in Columbia a few days later to show me a find he had unearthed while searching with his metal detector for artifacts near Columbia.

Mr. Frierson and I met at a farm supply store in Columbia where he handed me a box containing his treasure. I was almost speechless when I opened the small box. There, gently laid in a pillow of cotton, was an old fireman’s badge or medallion which was immediately obvious to me to be a relic dating back to our early history.

Mr. Frierson was very gracious and trusting to allow me to take his prized possession with me to begin researching its origin and eventual ownership. After getting home, my wife and research partner, Mary Jo, began looking at its detail with a magnifying glass. We knew from its designed that this was not a badge but rather some sort of medallion. The small metal ornament was imprinted and adorned with a hand-drawn ladder wagon on one side, a hand-drawn hose carriage on the other side, and a hand-drawn steam engine situated at the top of this work of art. Also engraved in its design was a speaking trumpet, a play pipe, ladders, a long-neck lantern, and a fireman’s helmet shield and flames imprinted at the top. Three holes, two at the top and one at the bottom still retaining a clasp, were observed, all lending belief that this item is a medallion rather than a badge. No marking or latch pin is found on the back.

I sent the photograph of the artifact to Daniel Maye, Chief Librarian of the FDNY Library, and Gary Urbanowicz, author of “Badges of the Bravest” and co-author “The Last Alarm: The History and Tradition of Supreme Sacrifice in the Fire Departments of New York City”. And, on a notion, I sent it to Chief Ronny Coleman, historian and former California State Fire Marshal, in hopes these experts could help in identifying its origin and eventual ownership.

They all responded with basically the same opinion: it is old and likely an artifact of the 1800s or early 1900s; it is a medallion much like we may see from early conventions or fire department competitions; ribbons and other labeling attachments probably complemented the main pendant. I am grateful to these gentlemen for their time and opinions.

Next came additional research to discover who, why, and other circumstances leading to its ultimate discovery near Columbia. From my own experience and knowledge, the medallion is not a native find from South Carolina or the South. Under this assumption, I began to research fire department badges and medallions of the North. Interestingly, I discovered that a large number of Northern volunteer firemen served in the Union Army fighting against the Confederate cause. Records from the annals of history reveal that firemen from across Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Lancaster, and York Counties) as well as New York State responded to President Lincoln’s appeal for 75,000 volunteers to defend the Union on April 15, 1861.

Among the most famous Northern groups of fireman to fight in the Civil War was the First New York Zouaves, or 11th Fire Zouaves. This group was organized under the leadership of Col. Elmer Ellsworth, a young Chicago State militiaman who, by the way, was not a fireman. According to writer Donald Collins, Ellsworth desired to recruit volunteer firemen because they were usually disciplined, brave and physically fit. Ellsworth wanted his men to stand out and to be different as soldiers of the Union Army, so he provided these volunteers with fancy uniforms similar to the French Zouaves having short blue jackets, baggy bloomer-like red trousers, reddish brown boots and red fez hats. It is noted that these colorful uniforms also made the firemen who wore them easy targets during the awful battles which were to come.

[caption id="attachment_8508" align="alignright" width="449"] Private Francis Brownell, a New York Firefighter serving in Union Army wearing badges and medallions[/caption]

Interestingly, Col. Ellsworth is reported to have been the first Union casualty of the Civil War. He was shot and killed by a tavern owner in Alexandria while removing a Confederate flag flying from the top of the bar. Private Francis E. Brownell, a New York fireman, pursued the tavern owner and killed him on the spot. A famous photograph of Brownell was taken where he stands in uniform adorned with his fire department badges and medallions in prominent view. A friend of President Lincoln, Ellsworth’s body was taken to Washington where it lay in state in the East Room of the White House.

The First New York Zouaves suffered significant losses at the Battle of Bull Run and many were killed, wounded, or captured as prisoners of war. About 30 of the New York Zouaves were seized and sent to Castle Pinckney outside of Charleston, South Carolina, where it had been prepared to serve as a prison. Civil War records indicate these volunteer firemen were an “exceptionally intelligent lot.” We are told both the guards and prisoners “treated one another with civility and respect.”

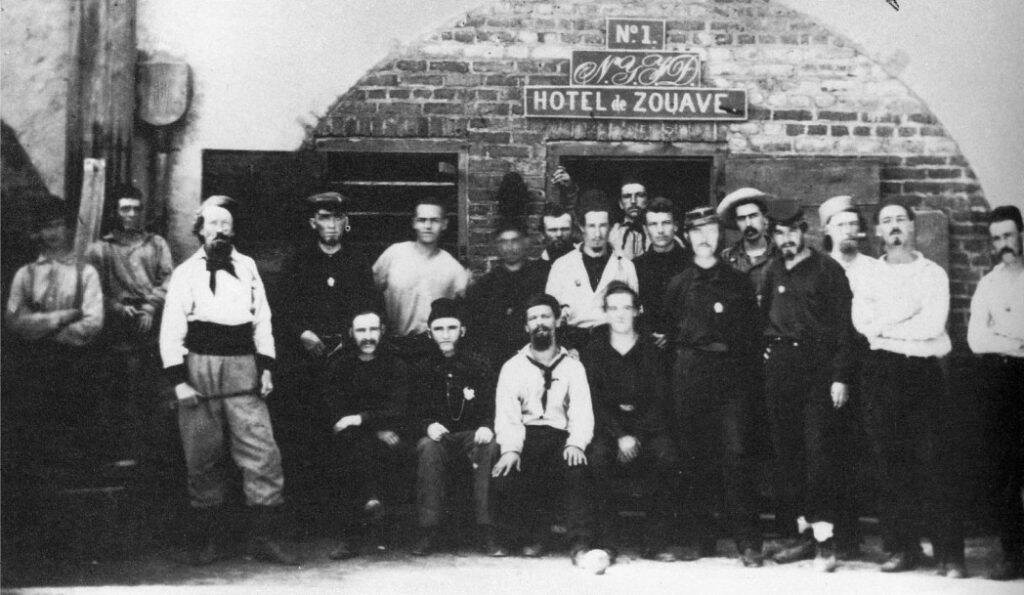

During their imprisonment, a photographer was found to take pictures of these prisoners in front of their quarters, over which they had placed a large sign having the inscription, “Hotel de Zouave”. After 155 years, this sign is now displayed in the FASNY Museum of Firefighting in Hudson, New York.

[caption id="attachment_8509" align="aligncenter" width="701"]

Private Francis Brownell, a New York Firefighter serving in Union Army wearing badges and medallions[/caption]

Interestingly, Col. Ellsworth is reported to have been the first Union casualty of the Civil War. He was shot and killed by a tavern owner in Alexandria while removing a Confederate flag flying from the top of the bar. Private Francis E. Brownell, a New York fireman, pursued the tavern owner and killed him on the spot. A famous photograph of Brownell was taken where he stands in uniform adorned with his fire department badges and medallions in prominent view. A friend of President Lincoln, Ellsworth’s body was taken to Washington where it lay in state in the East Room of the White House.

The First New York Zouaves suffered significant losses at the Battle of Bull Run and many were killed, wounded, or captured as prisoners of war. About 30 of the New York Zouaves were seized and sent to Castle Pinckney outside of Charleston, South Carolina, where it had been prepared to serve as a prison. Civil War records indicate these volunteer firemen were an “exceptionally intelligent lot.” We are told both the guards and prisoners “treated one another with civility and respect.”

During their imprisonment, a photographer was found to take pictures of these prisoners in front of their quarters, over which they had placed a large sign having the inscription, “Hotel de Zouave”. After 155 years, this sign is now displayed in the FASNY Museum of Firefighting in Hudson, New York.

[caption id="attachment_8509" align="aligncenter" width="701"] 1st New York Fire Zouaves captured at Battle of Bull Run and sent to Castle Pinckney near Charleston, S.C. Note: sign above prison door.[/caption]

Several of the New York Zouaves are pictured in front of the entrance to Castle Pinckney with at least one proudly wearing their badges and other medallions from their old fire companies in the North. My research has revealed that a fireman’s badge was, and still is, a sacred thing and was often carried into battle as a reminder of their former lives and oaths to protect lives and property. Today it would not be out of the question for a firefighter serving our military in Afghanistan or other deployment to carry his/her badge as a symbol of identity or affiliation. Personally, I carry in my pocket daily a fire department coin given to me by some particularly close friends as an icon of our brotherhood.

Very recently I found an article which tells the story of a Brooklyn fireman by the name of Duncan Richmond who volunteered in Ellsworth New York Zouaves. He was captured during the Battle of Bull Run and sent to the prison at Castle Pinckney. In 2008 or 2009, his badge was unearthed near Port Hudson, Louisiana. A researcher, Kevin Canberg, with the help of the Brooklyn Historical Society, traced the badge number to Duncan Richmond who served in the Union Army in Louisiana and fell in battle in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. He is buried in the Green-Wood Cemetery in New York City.

Chief Ronny Coleman (also a founding member of the National Fire Heritage Center in Emmitsburg, Maryland) relates that he found several stories about firefighters who carried their uniform badges into combat during the Civil War. Chief Coleman says in “the First Battle of Manassas, a soldier hid his badge in the stump of a tree and his friends had to go get it back for him.”

Well, this writer doesn’t have the mystery totally solved….yet. However, we know more about its place in history than at the beginning. I shall keep the reader informed as more of its obscurity is revealed. In the meantime, I shall continue to showcase this magnificent artifact as I travel the State sharing the stories of our colorful past.

Acknowledgements:

1st New York Fire Zouaves captured at Battle of Bull Run and sent to Castle Pinckney near Charleston, S.C. Note: sign above prison door.[/caption]

Several of the New York Zouaves are pictured in front of the entrance to Castle Pinckney with at least one proudly wearing their badges and other medallions from their old fire companies in the North. My research has revealed that a fireman’s badge was, and still is, a sacred thing and was often carried into battle as a reminder of their former lives and oaths to protect lives and property. Today it would not be out of the question for a firefighter serving our military in Afghanistan or other deployment to carry his/her badge as a symbol of identity or affiliation. Personally, I carry in my pocket daily a fire department coin given to me by some particularly close friends as an icon of our brotherhood.

Very recently I found an article which tells the story of a Brooklyn fireman by the name of Duncan Richmond who volunteered in Ellsworth New York Zouaves. He was captured during the Battle of Bull Run and sent to the prison at Castle Pinckney. In 2008 or 2009, his badge was unearthed near Port Hudson, Louisiana. A researcher, Kevin Canberg, with the help of the Brooklyn Historical Society, traced the badge number to Duncan Richmond who served in the Union Army in Louisiana and fell in battle in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. He is buried in the Green-Wood Cemetery in New York City.

Chief Ronny Coleman (also a founding member of the National Fire Heritage Center in Emmitsburg, Maryland) relates that he found several stories about firefighters who carried their uniform badges into combat during the Civil War. Chief Coleman says in “the First Battle of Manassas, a soldier hid his badge in the stump of a tree and his friends had to go get it back for him.”

Well, this writer doesn’t have the mystery totally solved….yet. However, we know more about its place in history than at the beginning. I shall keep the reader informed as more of its obscurity is revealed. In the meantime, I shall continue to showcase this magnificent artifact as I travel the State sharing the stories of our colorful past.

Acknowledgements:

Back to Firewire

Next Post

Back to Firewire

Next Post