March 27, 2020

Over the past several days, I have had the opportunity to listen to non-stop reporting, press conferences, endless analysts and pundits discussing the issues facing not only our country but the world as we are in the throes of our most recent pandemic known as the “coronavirus”, or “COVID-19.” Life as we know it has changed drastically in just a few short weeks and doesn’t show significant promises of normalcy for quite some time. To help breach my boredom, I have been listening to my portable radio as numerous medical calls for assistance are dispatched to my department. Most of these calls are not related to the COVID-19 virus, but in reality, some have the potential to create significant exposures to our firefighters and EMS personnel. We know it’s a given that Fire, EMS, Law Enforcement, and health care professionals are in high-risk jobs, and the dangers are increasing daily. While stuck at home, I decided to do some research to find out how the fire service coped with, and was impacted by, similar and much worse epidemics/pandemics/plagues over the last couple of centuries. Surprisingly I found volumes of material…much too much for purposes of this article. Health experts tell us, while there have been many outbreaks over time, they can narrow it down to five of the most punishing flu epidemics or pandemics in recent history. There was the “Russian Flu” pandemic which occurred in 1889 which killed over one million people worldwide. Then in 1918-1919 the “Spanish Flu” (most severe pandemic in recorded history) infected one third of the world’s population claiming nearly 100 million people, of which 675,000 U. S. citizens fell victim to the virus. More recently, the “Asian Flu” pandemic broke out in 1957-1958, claiming 1.1 million people worldwide with 116,000 in America. In 1968, the “Hong Kong Flu” made its appearance and lasted well into 1970. This pandemic also killed over one million throughout the world among which were 100,000 deaths in the United States. And, finally, in 2009 the “Swine Flu” (H1N1 pandemic) killed upwards of 575,000 throughout the world during the first year. A little recognized but very serious epidemic of yellow fever occurred in the United States in 1878 and was found to have been spread by a particular specie of mosquito. The launch of yellow fever was initially observed in the southern region of the United States where its epicenter was located around New Orleans. Unseasonably warm temperatures presented favorable conditions for the breeding of mosquitoes and the eventual spread of yellow fever.

Conditions in New Orleans were ripe for the spread of the disease up the Mississippi corridor into the north due to its heavy trade traffic. Disease-carrying mosquitoes traveled up the Mississippi as far north as St. Louis, New York, Philadelphia, and really hit Memphis with a vengeance. According to authors Henry Diaz and Gregory McCabe, “the yellow fever outbreak greatly contributed to the financial collapse of Memphis in 1878” and brought about failure of its government services. The health of the firemen in these larger cities crushed their abilities to perform their duties. The City of Memphis was so strained financially that an appeal was made for financial assistance in order to provide for their firemen and dependents. The Detroit Free Press reported in the September 8, 1878 edition that the Detroit Fire Department answered the call by sending a donation to Memphis Fire Chief McFadden for the relief of their suffering brothers. Interestingly, as summer turned to fall, and winter approached with frost chilling the air, the yellow fever epidemic began to diminish its rage. During the “Spanish Flu” pandemic outbreak in 1918 and 1919, New Orleans was hard hit again with over 50,000 diagnosed cases and 3,489 disease related deaths. Research revealed that during the first week of September 1918,

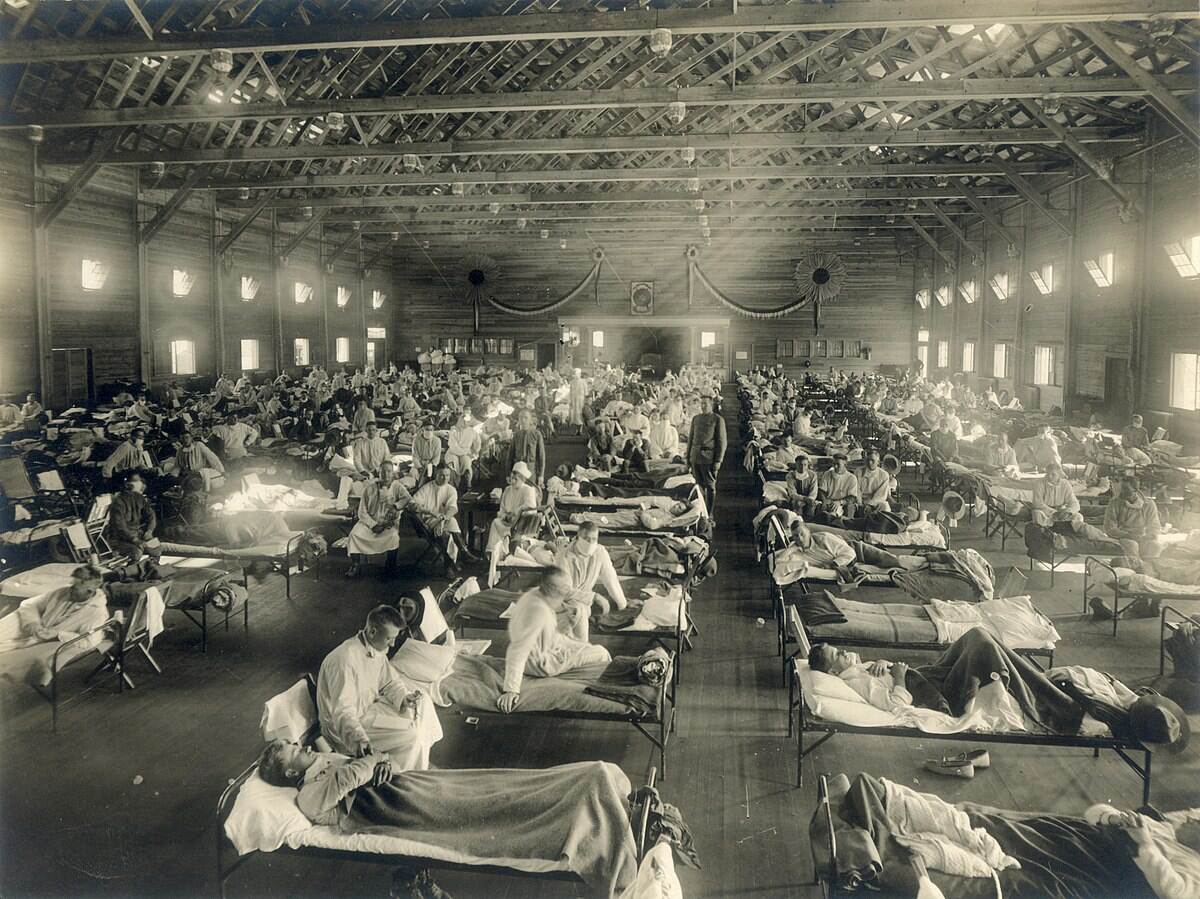

Conditions in New Orleans were ripe for the spread of the disease up the Mississippi corridor into the north due to its heavy trade traffic. Disease-carrying mosquitoes traveled up the Mississippi as far north as St. Louis, New York, Philadelphia, and really hit Memphis with a vengeance. According to authors Henry Diaz and Gregory McCabe, “the yellow fever outbreak greatly contributed to the financial collapse of Memphis in 1878” and brought about failure of its government services. The health of the firemen in these larger cities crushed their abilities to perform their duties. The City of Memphis was so strained financially that an appeal was made for financial assistance in order to provide for their firemen and dependents. The Detroit Free Press reported in the September 8, 1878 edition that the Detroit Fire Department answered the call by sending a donation to Memphis Fire Chief McFadden for the relief of their suffering brothers. Interestingly, as summer turned to fall, and winter approached with frost chilling the air, the yellow fever epidemic began to diminish its rage. During the “Spanish Flu” pandemic outbreak in 1918 and 1919, New Orleans was hard hit again with over 50,000 diagnosed cases and 3,489 disease related deaths. Research revealed that during the first week of September 1918, the city government and Board of Health “ceased to function.” Among the officials to contract the virus was Mayor Flippin and Chief of Police Philip Athey. Of the 41 police remaining in the city, only 7 were “fit for duty,” and “the fire department’s number was cut to 13” out of nearly 2,000 firemen and auxiliary members. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh probably were the most impacted with higher death rates. In order to assist in curbing the spread of the pandemic, schools were shut down, theaters and pool halls were closed, stores shuttered their doors, and public gatherings were outlawed. Of course, there was opposition from the business community due to the substantial impact on their economy. The public was encouraged to wash hands frequently and to quarantine the sick. The goal of the medical community in those days was not unlike today…to “flatten the curve” (a term even used 102 years ago) and keep the pandemic from exploding. In San Francisco health officials required every citizen to wear a gauze mask, and the police were authorized to fine anyone caught without a mask a $5.00 penalty for ignoring this necessity. Essential services such as police and fire were severely hindered by shortages of personnel. Author John Clayton said in Manchester, N. H. that, “fire departments were overwhelmed.” The Kentucky Post reported in October of 1918 that “flushing the streets by fire hose was urged. Major John J. Craig stated that the fire hoses had gotten more use in two weeks than they had in the previous two years.” In Honolulu, the Board of Health quarantined the Chinatown section of the city and practiced the burning of garbage, only to have started a conflagration which destroyed some 4,000 homes. In 1918, New Orleans Fire Chief Thomas O’Conner released a letter written by fire department President I. N. Marks. The letter reads as follows: “To the Fire Departments of the Union, and All Other kindred Charitable Organizations: The Fire Department of New Orleans, for the first time in its half-century of existence, is compelled to make a public appeal for aid. With its 2,500 active and exempt members and their families, with 270 widows, 375 orphans and half orphans; with the inability of the city to pay the department; with an empty treasury and a widespread epidemic prevailing; it finds itself powerless to properly relieve the sick and distressed. In the cause of humanity it therefore appeals to kindred charitable organizations throughout the country for such assistance as they can render.” As a result of this appeal the Detroit Fire Department once again responded with a beneficent gift of $126.00. Other departments throughout the country untouched by the epidemic answered with great generosity. Probably the most shocking of pandemics to ever rock America was not of a human virus variety but rather a disease affecting only horses and in many cases, mules. This occurrence lingers in history, basically forgotten, and utterly unfamiliar to nearly everyone today because horses play a less significant role in modern lives than 150 years ago.

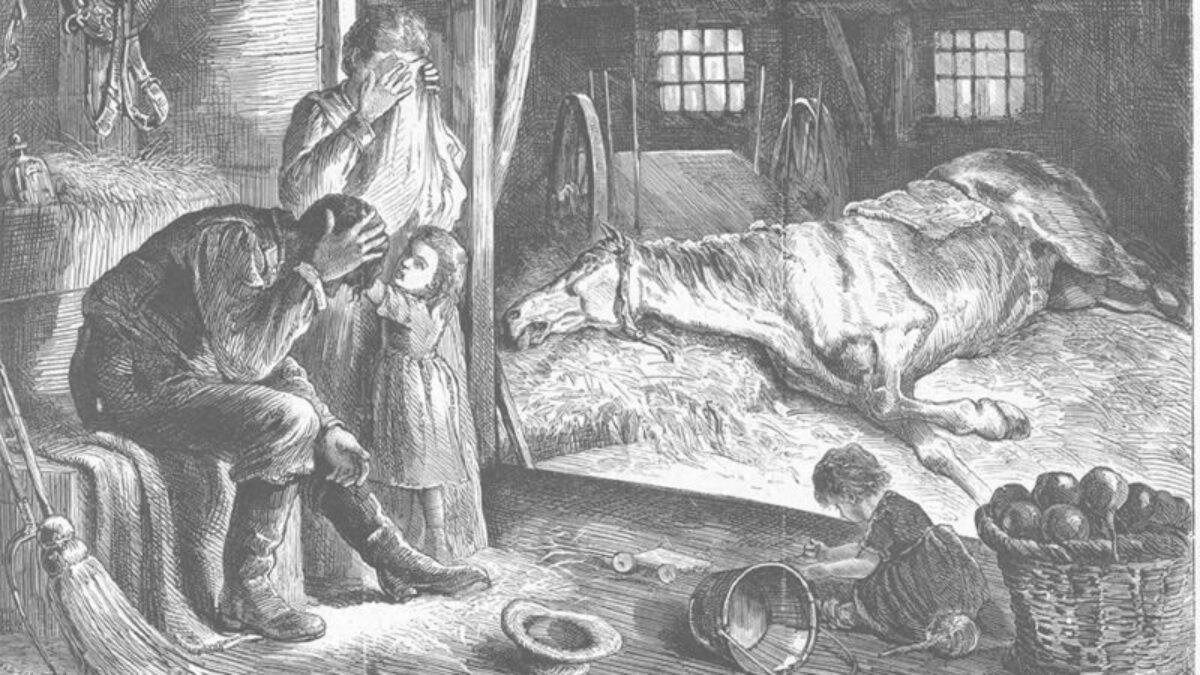

the city government and Board of Health “ceased to function.” Among the officials to contract the virus was Mayor Flippin and Chief of Police Philip Athey. Of the 41 police remaining in the city, only 7 were “fit for duty,” and “the fire department’s number was cut to 13” out of nearly 2,000 firemen and auxiliary members. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh probably were the most impacted with higher death rates. In order to assist in curbing the spread of the pandemic, schools were shut down, theaters and pool halls were closed, stores shuttered their doors, and public gatherings were outlawed. Of course, there was opposition from the business community due to the substantial impact on their economy. The public was encouraged to wash hands frequently and to quarantine the sick. The goal of the medical community in those days was not unlike today…to “flatten the curve” (a term even used 102 years ago) and keep the pandemic from exploding. In San Francisco health officials required every citizen to wear a gauze mask, and the police were authorized to fine anyone caught without a mask a $5.00 penalty for ignoring this necessity. Essential services such as police and fire were severely hindered by shortages of personnel. Author John Clayton said in Manchester, N. H. that, “fire departments were overwhelmed.” The Kentucky Post reported in October of 1918 that “flushing the streets by fire hose was urged. Major John J. Craig stated that the fire hoses had gotten more use in two weeks than they had in the previous two years.” In Honolulu, the Board of Health quarantined the Chinatown section of the city and practiced the burning of garbage, only to have started a conflagration which destroyed some 4,000 homes. In 1918, New Orleans Fire Chief Thomas O’Conner released a letter written by fire department President I. N. Marks. The letter reads as follows: “To the Fire Departments of the Union, and All Other kindred Charitable Organizations: The Fire Department of New Orleans, for the first time in its half-century of existence, is compelled to make a public appeal for aid. With its 2,500 active and exempt members and their families, with 270 widows, 375 orphans and half orphans; with the inability of the city to pay the department; with an empty treasury and a widespread epidemic prevailing; it finds itself powerless to properly relieve the sick and distressed. In the cause of humanity it therefore appeals to kindred charitable organizations throughout the country for such assistance as they can render.” As a result of this appeal the Detroit Fire Department once again responded with a beneficent gift of $126.00. Other departments throughout the country untouched by the epidemic answered with great generosity. Probably the most shocking of pandemics to ever rock America was not of a human virus variety but rather a disease affecting only horses and in many cases, mules. This occurrence lingers in history, basically forgotten, and utterly unfamiliar to nearly everyone today because horses play a less significant role in modern lives than 150 years ago.

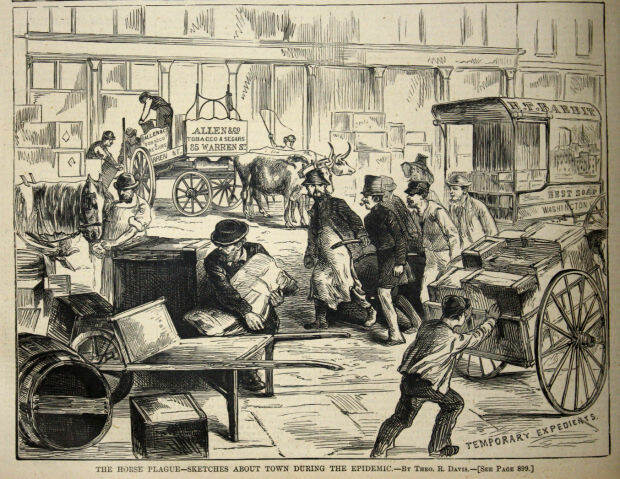

Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1872

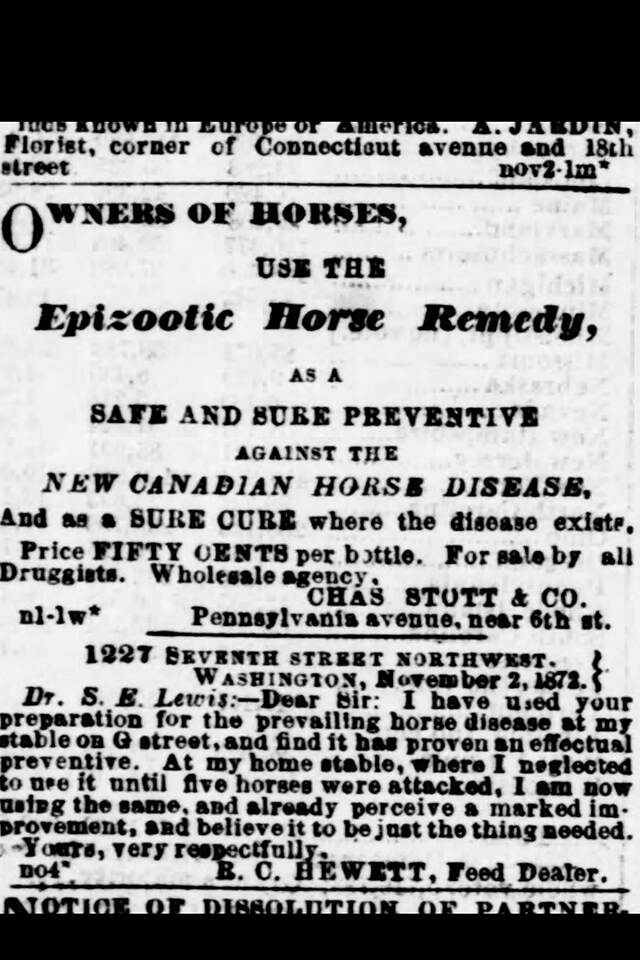

However, this outbreak in North America and Canada literally brought the United States economy to a full and complete stop. “The Great Epizootic”, as it was called, was a form of equine flu. Restoration specialist, Kevin Durkin, explains, “when a disease that affects animals reaches widespread proportions, it is known not as an “epidemic”, but an “epizootic.” The disease initially broke out in Toronto, Canada, in late summer and spread very quickly across America in just a matter of days between the months of October and December of 1872. The disease reached South Carolina on November 6, 1872. And, by November 30th, the disease had stricken the horses in the City of Newberry. Estimates are between 80% and 99% of all horses nationwide were affected with upwards of a 10% mortality rate. The main symptoms of the virus were lethargy and extreme weakness. “It’s first noticeable symptoms were a flow of tears from the eyes, a watery discharge from the nose, and general tiredness, followed by a cough.” Horses simply became so weak to the point they could not stand or eat.

During this time of population growth in America, horses “powered the economy.” According to a study completed by the Long Riders Guild, seaports and transportation came to a standstill; trains could not run as coal could not be conveyed to power them. Fire departments required volunteer citizens to pull their steam engines, ladder trucks, and hose wagons. The New York Times reported on October 24, 1872, that “it is not uncommon along the streets of the city to see horses dragging along with drooping heads and at intervals coughing violently.” The newspaper headlines read “Alarming Effect Upon the People;” “Total Suspension of Travel;” “Disappearance of Wagons.” The writer continued his reporting with staggering data that “the fatality rate arising from the epidemic is on the increase in Boston with deaths averaging 25 to 30 (horses) daily.” At a time in history when the fire service had transitioned from hand-drawn engines to horse-drawn apparatus, the toll of the horse epidemic on America’s firemen was beyond belief. The Long Riders Guild said it best…”one of the major casualties of the Great Epizootic was the City of Boston itself. A great fire swept through the industrial section on November 9, 1872…” and destroyed over 750 buildings in just sixteen hours and left 1,000 homeless. Fourteen people died, including eleven firemen. John Connolly, research librarian and writer, described vividly that the horses of the Boston Fire Department that pulled those massive engines, hook and ladder trucks, and hose wagons to alarms of fire were “out of service” and unable to perform their duties. As a result, the fire department was compelled to draft citizen volunteers to pull their machines to locations around the city in order to set up operations to finally attack the conflagration which was already beyond control. The same day of the Boston fire, the Chicago Tribune reported in their city, “the fire department horses are suffering all the severity of the disease. Four horses have died, and many are at a crisis. Yesterday morning a horse driven by 2nd Assistant Marshal Petrie fell dead in his stall. These horses have had excellent treatment, but they have been compelled to make a number of runs that have rendered the treatment of little effect.” Five days later, the Chicago Tribune reported from Milwaukee, Wisconsin that the “officers of the fire department have purchased six yoke of oxen and today issued a call for volunteers to render assistance in case of emergency.” And, from Louisville, Kentucky, “more than 1,000 horses are now affected. Mules are being afflicted about as badly as horses. The Fire Committee of the Common Council tonight called meetings of citizens of each ward to organize companies of citizens to draw the engines to fires in case of emergency. Nearly all the horses in the fire department are down with the disease.”

In Columbus, Ohio, on November 19, 1872, it was reported that “the horse disease is well under way. The street cars are being withdrawn and there are no horses to hire in the livery stables. Provisions are being made for hauling the fire engines by hand.” The Wisconsin State Journal published on November 20, 1872, that “the progress of this equine malady in the principal cities and towns of the country has seriously interfered with travel and traffic, and it was doubtless owing in a great measure to it that the Boston fire was not sooner subdued.” Fire chiefs from across the country offered assistance when feasible to the City of Memphis which was devastated by the horse disease. Chief Engineer of the Nashville Fire Department, S. B. Randall, wrote “a resolution was passed tendering to you our services and aid in any branch of your department that you may deem to be the most useful.” On November 21, 1872, The Charleston (S.C.) Daily News reported “the epizootic is increasing at Columbia” with the added commentary that “the physicians are footing it.” And, on December 6, an Iowa newspaper commented “on account of the epizootic, the Mayor of Davenport calls on all able-bodied men to report at the engine house in case of fire.” On December 10th, The Leavenworth Times (Kansas) said “Kansas City had a $30,000 fire Saturday night. The Phoenix mills were entirely destroyed. The engines had to be taken by hand to the fire, as all the horses were down with the epizootic.” An Illinois paper ran a story on December 13th that “the Chief of the St. Louis fire department has enlisted twenty-five men for each steam fire engine to serve until the horse disease abates. They will take the place of the horses to haul steamers to fires.” In the same article, the writer shared “there was a $125,000 fire in St. Louis yesterday. It originated at 409 North Third Street, and the escape from a general conflagration was a narrow one. On account of the epizootic the fire engines had to be hauled to the scene by men.” Into the spring of 1873 the horse disease continued to plague the country. The San Francisco Examiner reported on April 22nd that “the epizootic is still in the ascendant, and we learn that it is steadily increasing, stables that on yesterday had but few cases, today, are filled with coughing horses, all sick, and in a mournful condition. Two horses in the Fire Department were taken down with it yesterday…one in Engine 4, and one in Engine 10. In case the disease becomes general in the Department, the apparatus will be drawn with ropes.” Well, times may change but the magnitude of the challenges that has always faced the fire service remains basically the same. Back in the day, Incident Action Plans (IAPs), National Incident Management System (NIMS), State Emergency Operations Center (SEOC) were unheard of concepts and processes to our ancestors. But, yet, they always stepped up to meet their challenges just as we do today. During the “Spanish Flu Pandemic” of 1918 one can be assured that the fire bosses attempted to put measures in place to make sure their firemen were best positioned to continue working and not end up a casualty of the virus. Although we may be stretched thin and having to consider changing the way we do business, South Carolina’s fire service is up to the task. With the help of our first responder partners, local, state and national leaders we will come through this storm as our forefathers did in their day. Stay safe out there!

Back to Firewire

Next Post

Back to Firewire

Next Post